Image credit: Stocksnap

Image credit: Stocksnap

Over the last few months, there have been so many unwritten blog posts. They glide around like ghosts, and this post was almost one of the ghosts because who writes about their new year’s resolutions in February? (Chronically tardy people, that’s who. Which is a perfect description of me.)

Since my last (non-book review) post, I have turned 40. Jon planned a birthday trip for me in Michigan’s wine country, which was amazing and one of my favorite moments of 2018. I’ve read a lot—an odd combination of mysteries and nonfiction. I’ve started on a weight loss journey, and started an Instagram account to document it. I celebrated the new year in a jazz club in Detroit. And I have made resolutions, which I have procrastinated on sharing for approximately 8 weeks now. Here they are:

Resolution 1: Appreciate my body more, flaws and all.

I threw my shapewear in the trash on New Year’s Eve.

I was in a jazz club with my husband, perched stiffly on a bar stool due to my shapewear. I looked around the jazz club and there were women of all sizes wearing their sexiest clothes, and I was done being immobile in my dress due to fear that my fat rolls might be on display. So, I went into the bathroom and trashed my shapewear. And it was liberating.

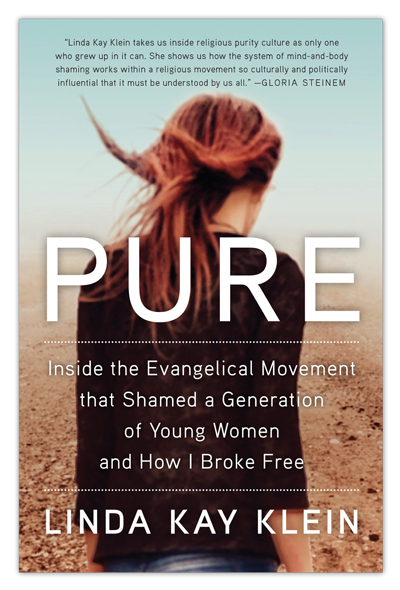

I may not be at my ideal weight, but my body has always been good to me. My body is strong, and I’m rarely sick. My last book review on the blog (Pure by Laura Kay Klein) and my next planned book review (Hunger by Roxane Gay) both focus on body shame and moving past it. Because life is too short to be uncomfortable in your own skin.

Resolution 2: Do less around the house.

I spend most of my life focused on what I’ve left undone, whether it’s the bathrooms I haven’t cleaned or the phone call I haven’t made or the writing project I haven’t started. Something needs to go.

There are four able-bodied people in my house, and there is no reason that I should be responsible for the great majority of the cleaning.

Resolution 3: Try more independent restaurants in my town.

An unflattering thing about myself: I tend to be kind of grumpy about where I live. I moved to Canton five years ago, when I got married, and I was less than thrilled about leaving Ann Arbor. The suburbs are great if you enjoy SUVs the size of tanks, happy hour at Applebee’s, leisurely strolls through Hobby Lobby, and maximizing your Kohl’s Cash. (Disclosure: I have no idea what Kohl’s Cash is, and I plan to keep it that way.) I’m not that person, so the things I love about Canton are limited to my house, the library, and my gym.

I want to find in joy in the place where I live. Canton is not cool and neither am I, and that’s perfectly fine. But here is a stealthy cool thing about Canton: It’s diverse.

This is where the restaurants come in.

While Canton does have abundance of chain restaurants, there is also a lot of independent restaurants too. They are in strip meals and are generally nothing to look at, but given the high number of immigrants in Canton, they are authentic. Aside from the Indian restaurants closest to my house and a few sushi places I have frequented when Jon is out of town, I largely have not gone to these places. My husband has the most Midwestern palate of anyone I know, and this largely limits where we eat as a family, but going forward I am venturing out even if it means dining alone. And with each meal, I will experience something new about Canton.

Looking at all three of my resolutions, I think this year is about loving my life as it is. It’s definitely not a “burn it all down” year, but a year for contentment and happiness.